“When we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard or welcomed. But when we are silent, we are still afraid. So it is better to speak.” ~Audre Lorde

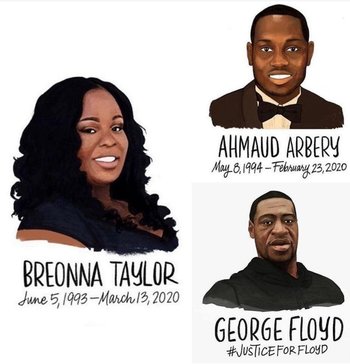

Black Americans have witnessed and learned of a lot of racial violence over the past few weeks. From the murder of Ahmaud Arbery by neighborhood vigialantes to the recent police murder of George Floyd, we continue to be reminded that our lives are not deemed valuable. It’s all been too much. Hostility and violence against black people in this country is a societal norm that comes in all forms; from being questioned about occupying public spaces, experiencing discriminatory behavior at work, to being harassed by police. It’s exhausting, angering, saddening and can cause mental and physical distress. Consistently fearing that your mere presence will incur hostility from those who deem you a threat, with no provocation, is a tiring experience, but one the black community is used to. I’ve encountered more than my share of “Karens” and “Kens” in the world.

Watching Amy Cooper purposefully weaponize race and call the police on Christian Cooper in Central Park, feigning distress and lying about being threatened by him, made me recall difficult memories of times I was “Karen-ed” as well.

I remember working at Viacom for one of the channels as an administrative assistant and overhearing a white woman in management tell my black coworker to watch me to make sure I didn’t take anything. I was shocked. I hadn’t done anything to make her think I was a thief. I didn’t know why she targeted me. I reported her to my manager who seemed concerned, but don’t remember anything happening to her. I also remember being stopped by security in the hallway on my way to lunch because I didn’t “look” like I worked there. Those are just two examples of the kind of racially based harassment I endured while working there among other places. Last year I worked at two libraries and was “Karen-ed” every single day.

At one library my young, white supervisor over disciplined me and wrote me up nearly every week for one bogus infraction after another. After our one-on-one’s I was routinely walked up to the office of the director, another “Karen”, who would try to intimidate me and make me the problem, never addressing my supervisor’s inappropriate behavior. From publicly chastising me about rules I wasn’t aware of to nitpicking my attire, my former supervisor attempted to critique me into submission. I finally wrote a 3-page document outlining the abuse and reported her to the board. After that, I no longer had issues with her. At the next library my experience was similar. Those managers were merely examples of the many white women I’ve had to deal with who viewed my blackness as a threat, something they had to subdue. From grade school to the workplace, like most African Americans, I’ve had to deal with systemic racism that aims to put me in my place.

The incidents and energy required to fight back takes an emotional and psychological toll over time. I’ve suffered depression, anxiety and PTSD from toxic workspaces that were populated by people who have very specific ideas about black people and how we should show up. These latest instances where black life has been snuffed out and devalued by racists only compounds feelings of anger, hurt and helplessness. So what do we do with these feelings? What do we do with our suffering?

Like generations before, we cope, we move on, move through, gather with community and worship. Some of us seek support, some of us become activists, and some of us just accept that this is what life is when you’re black. There’s no one, linear path to healing, but there is something to keep in mind.

Knowing your value is crucial to surviving a world that has deemed you worthless. With every teacher, professor, supervisor, “Karen” or “Ken” who treated me like I was less than, I had to hold to the fact I was more than; more than their stereotypes, more than their fears, and more than their beliefs about me. That’s what motivated me to stand my ground. And even when I’ve been flattened with depression navigating racist experiences, I still know I am valuable, which serves as the epicenter of my ongoing healing. And when it comes to healing from constant exposure to racist acts across the country I believe part of that process is acknowledging the pain and expressing it.

Whether you journal or write about your feelings, talk with friends or a therapist, create art that encapsulates your hurt, engage as an activist, or post on social media, having a voice is important in the journey of healing racial trauma. In a world that treats black people like objects to oppress and conquer, part of the path to coping and healing is knowing your worth and having your say.

Social Menu